As a writer whose job is to be creative every day, procrastination comes pretty naturally to me. The line between working hard and hardly working is rather thin in my case, and, at different points in life, I played jump rope with it whenever I felt overwhelmed with my tasks.

Much like most people, I spent hours upon hours procrastinating, and whenever I felt guilty, I then spent even more time trying to figure out — why do people procrastinate anyway?

Eager to learn why procrastination is such a common struggle, I researched this topic extensively and contacted experts to share their insights with me.

As my own experience and scientific research have confirmed, our mood plays a much larger role in our tendency to procrastinate than we think. In fact, procrastination is a strategic choice we make to instantly feel better — no matter the consequences.

Let’s dive into this matter without any delay!

What procrastination is — and isn’t

Procrastination is a self-regulation problem that involves needlessly and voluntarily delaying intended tasks even though we may face negative consequences.

Now, we’ve always known that procrastination constitutes some sort of delay of important tasks. However, accuracy is crucial here.

Procrastination always involves a delay, but not all delays are automatically acts of procrastination.

To that end, delaying an assignment because of a family issue isn’t procrastination, as that delay is absolutely necessary. Similarly, if your manager tells you to switch to another assignment and put off your current one, that’s not procrastination either. It’s not your choice!

For a clearer explanation, I turned to the expertise of Fuschia Sirois, PhD, Professor of Social and Health Psychology at Durham University, and her book Procrastination: What It Is, Why It’s a Problem, and What You Can Do About It.

So how do you know if you’re actually procrastinating? Well, in her book, Sirois explains that you might be if:

- You intended to complete the tasks you’re now delaying,

- You’re delaying tasks without any particular need,

- No one is urging you to delay, and

- You’re aware there may be negative consequences for your behavior.

That’s right — procrastination involves negative consequences, either for yourself or for others. This distinction is crucial in determining the differences between common delays and true procrastination.

The myth of beneficial procrastination

As Sirois further explains in her book, procrastination can never be a good thing. It always has some sort of negative impact — even when the consequences aren’t readily apparent.

So what we may see as active or positive procrastination is usually just a switch to problem-solving mode. Naturally, solving a problem often leads to a better, more positive outcome.

For example, if you were to postpone a presentation at work because you lack key information, you wouldn’t be procrastinating.

In that case, you’re making a wise delay — a strategic switch to solving the problem at hand, which is obtaining more information to ensure the success of your presentation. So, you’re benefiting from this delay!

What is the root cause of procrastination?

Timothy Pychyl, PhD, a retired Professor of Psychology at Carleton University, is another world-leading expert in the field of procrastination. Together with Fuschia Sirois, they explored how people prioritize short-term mood regulation when procrastinating. According to these experts, the root cause of procrastination is our emotional state.

Essentially, procrastination is more about mood management rather than time management or laziness. And that notion tracks when you consider how irrational procrastination is at its core.

As Sirois reveals, irrationality led her and her colleagues to examine the idea of emotions being at the core of procrastination:

“Why would you unnecessarily delay something? Why would you delay something, especially if it’s important and especially if you know there will be negative consequences? There is no rational reason, and there’s no formula you can come up with that will give you that type of delay.”

While researching procrastination, it soon became evident that the team should focus on examining what else was irrational in human behavior and nature — which is our emotions:

“Emotions are irrational, and emotions don’t make sense. So when you do something that’s harmful to you and have the sense that it’s harmful to you, you’re not thinking logically. You’re not planning this.”

That said, not every type of emotion leads to procrastination. Over the years, Sirois’s research showed that procrastination revolves around negative emotions:

“We looked at some of the evidence in terms of what people do when they are faced with tasks that are unpleasant, and we’ve looked at the evidence suggesting that people don’t delay things that are fun or exciting and they want to do. They delay things that are troubling and difficult, or unstimulating, or stressful.”

But how exactly do we use procrastination to protect ourselves from negative emotions? As it turns out — it’s a rather simple choice.

Procrastination as a way of avoiding negative emotions

When negative emotions hit, we can either manage them and get on with the task or procrastinate. According to Sirois, we choose to delay tasks we feel negatively about.

In other words, we tend to procrastinate when we cannot effectively respond to and deal with negative emotions.

In the ideal world, we would all know how to deal with all those negative emotions. However, some people don’t, so they resort to procrastination — which enables short-term mood repair:

“We prioritize our goal of feeling less terrible than we are right now thinking about this task. And the easiest way to do that is to use a common coping strategy, which is avoidance. Procrastination at its core can be thought of as an avoidance coping strategy.”

So, as Sirois explains, the focus isn’t on the task at hand anymore:

“Your goals are going to shift from ‘I need to get this task done as unpleasant as it is’ to ‘I need to manage the emotions that are coming up when I do this task.’“

What is the source of these negative emotions that may lead to procrastination?

The million-dollar question here is: if negative emotions and our inability to manage them lead to procrastination, what is the exact source of those negative emotions?

As Sirois explains in her book, 2 main contributors are at play:

- The way we evaluate our tasks, and

- How we evaluate ourselves in relation to our tasks.

Now, people view tasks differently, and what’s aversive to me may not be so aversive to you. However, it has been shown that the kinds of tasks procrastinators tend to avoid are usually:

- Boring,

- Stressful,

- Difficult,

- Frustrating,

- Uncertain, or

- Not as meaningful as their other tasks.

That said, procrastinators could also choose to delay certain tasks because of how these tasks make them feel about themselves.

Depending on your mindset, you could have a rather simple task at hand and still prefer to delay it because it points out your own shortcomings. This, in turn, makes you feel:

- Shame,

- Guilt,

- Dread, and so on.

What’s more, some have a tendency to use a “psychological crystal ball” to determine how they might feel about a task in the future — and then procrastinate to avoid those emotions.

This phenomenon, which psychologists call affective forecasting, refers to the emotional time travel many procrastinators take part in. And as Sirois explains, just expecting negative emotions could be a good enough excuse for a delay:

“We’re the victims of our own mind in some ways. We create a narrative around what that task is going to be like, and that’s enough to make us feel bad about it, so we want to put it aside.”

How procrastination robs you of your health and goals

As established, procrastination provides an immediate hedonic reward — a huge sense of emotional relief — because it lets us temporarily disconnect from our negative emotions. However, this comes at the expense of our long-term goals and health.

Overall productivity loss is just one of the many consequences. Indeed, procrastination can affect work performance and even your rapport with other professionals in your field. This, in turn, can change the trajectory of your professional career.

Perhaps more importantly, studies show that procrastination can affect our overall well-being.

In her research on procrastination and stress, Sirois emphasized that the risk of procrastination is higher in stressful contexts. It’s no wonder then that her research has also shown that procrastination could be a vulnerability factor for hypertension and cardiovascular disease:

“I looked at poor heart health because it made sense. People who have poor stress management and don’t engage in proper health behaviors are going to be on a trajectory towards poor heart health, and also potentially obesity.”

A recent study on the links between procrastination and health outcomes revealed that higher levels of procrastination are also associated with:

- Worse subsequent mental health (stress, anxiety, and depression),

- Unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, and

- Disabling pain in the upper extremities.

Unsurprisingly, high levels of stress are, in particular, linked to procrastination. As Sirois explains, that, along with other unhealthy patterns, can lead to long-term consequences:

“Any long-term or chronic condition that has high levels of stress and a lack of engaging in healthy eating and healthy behaviors, which of course can lead to poor sleep, is a potential long-term health outcome of procrastination.”

Furthermore, in her book, Sirois mentions that chronic procrastinators are also less likely to seek help for these issues. As a result, procrastination presents a recovery barrier for people struggling with mental health.

Social effects of procrastination

Procrastination can also have strong psychological effects on us due to societal norms.

As Sirois explains, procrastinators often feel a high level of guilt and shame due to their procrastinating ways:

“When people procrastinate, they feel bad about it. And the reason they feel bad are the shame and guilt that kick in. These are sort of embedded in the social norms we have about being productive.”

You only need to consider today’s publishing industry to realize how strongly the world associates productivity with being a good person — hence, procrastination with being a bad person:

“We live in a time now where every other week, there’s a new book coming out about how to squeeze 10 more minutes into your day and how to be more productive. Some of them come at it from healthy stances, some of them come from less than healthy stances, but all of them have the same underlying ethos — being more productive is better.”

What factors make you more likely to procrastinate?

It’s clear that procrastination affects our lives negatively. Knowing that — why on Earth do we still do it?

Do procrastinators lack time management skills — or are they just lazy?

A popular — but nevertheless erroneous — belief that’s become prevalent among productivity gurus and in the press is that procrastination is a side effect of poor time management or even laziness.

Imagine if that were true. The solution would then be to become better at organization, avoid social media and other similar distractions, become an early riser, and so on, right?

And yet — if procrastinators are so lazy, wouldn’t they be lazy about the stuff they love to do too? What’s more, if they’re never punctual, wouldn’t they be always late even when they’re off to do something fun?

Evidently, laziness and poor time management have little to do with delaying tasks. So what contributes to our procrastination tendencies then?

Are procrastinators just impulsive?

Many different causes of procrastination have been suggested over the years, including personality traits such as impulsivity and temporal discounting — which is preferring instant rewards over future benefits.

However, according to Sirois, impulsivity cannot be the cause but rather a contributing factor:

“A lot of people say that impulsivity is the cause of procrastination, but it’s not. It’s a factor that contributes to making it easier to procrastinate, but that’s not what drives you to procrastinate. What drives you is that inability to manage those negative emotions attached to the task. And if you’re impulsive, it means you’re not going to stop and think about how you could manage those negative emotions — you’re just going to react and disengage.“

Does it all come down to our personalities?

You may also think that some people are just more prone to procrastination because of the way they are. And you wouldn’t be too far from the truth!

As Sirois explains, your personality could increase your tendency to procrastinate:

“If we’re talking about procrastination as a chronic tendency, one easy way to think about it is as a personality trait. And like most personality traits, they’re not bread and bone. They shift and morph over time, and tons of research shows this. This could happen developmentally across different life stages, or [due to some] events in your life.”

Further reading:

Could some personality types be more productive than others? Learn about the 15 MBTI personality types and their characteristics in the post below:

Are genetics to blame for our procrastination habit?

As Sirois notes, both our genes and environment have an equal input into our tendencies:

“Some of the evidence that’s been looked at regarding twins that were raised apart — which is a good way to find out how much is nature and how much is nurture — found that procrastination is a chronic tendency in terms of how it expresses itself, [which is] phenotypically. There isn’t a procrastination gene, but if we look at the behavior that characterizes a trait — phenotypic expression — researchers have found that there is about 46% of heritability.”

Genes may contribute to procrastination in a few different ways:

“Some people have a lower threshold for negative stimuli. So, those individuals might be more apt to have that sort of knee-jerk reaction to negative emotions and want to procrastinate.”

Another way genetics play a role in procrastination is via neurological conditions, such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). According to Sirois, this happens due to a failure of emotion regulation:

“For a while now, we’ve known that people with ADHD struggle more with procrastination, so there’s that whole neurodiversity angle. Initially, it was thought that it was because they’re so distractible. But now, [we know] one of the core defining features of ADHD is emotion dysregulation. And again, that just fits with our theory on what causes procrastination.”

Can our upbringing impact our procrastination tendencies?

As for the environmental input, Sirois mentions the models of self-regulation that someone may have grown up with in their family:

“If people in your family didn’t regulate negative emotions very well — maybe they did it in a very loud, outward way that was threatening — or they just hid [their emotions] and you had no idea what to do when you felt bad because nobody really showed you how to manage those negative emotions — there can certainly be developmental trajectories from childhood experiences that could lead into procrastination.”

Does being productive in any other area make you less of a procrastinator?

Unfortunately, procrastination is usually seen as a character flaw and moral failing. So, if you choose to be productive in any way you can — you’re not procrastinating, right?

Well, no.

Not all procrastinators choose to have fun or otherwise waste time instead of doing their work. In fact, procrastinators such as yours truly would effectively switch out aversive tasks for seemingly more beneficial ones — like exercising 3 times a day — to “keep up the appearances” of being productive.

But, according to Sirois, doing something you say it’s for your well-being doesn’t make it a better excuse to procrastinate:

“A classic example we have is that people procrastinate because they want to do stuff that’s fun, like going to a party, binge-watching Netflix, or playing video games. We see those tasks as largely unhealthy — but they could just as easily be replaced with exercising 3 times a day and doing all of these other things so that you can say ‘I’m feeling good.’”

So, even though doing anything seems better than doing nothing, the gist is the same. You’re not facing the real reason you’re procrastinating:

“What you’re trying to do with all these alternative tasks — these feel-good tasks — is mask the negative emotions. You’re not actually dealing and processing. And I think that’s the other key point there. There’s nothing wrong with working on our well-being. […] But if those tasks now become an excuse for not doing what you’re supposed to be doing […] — then that’s not exactly healthy either.”

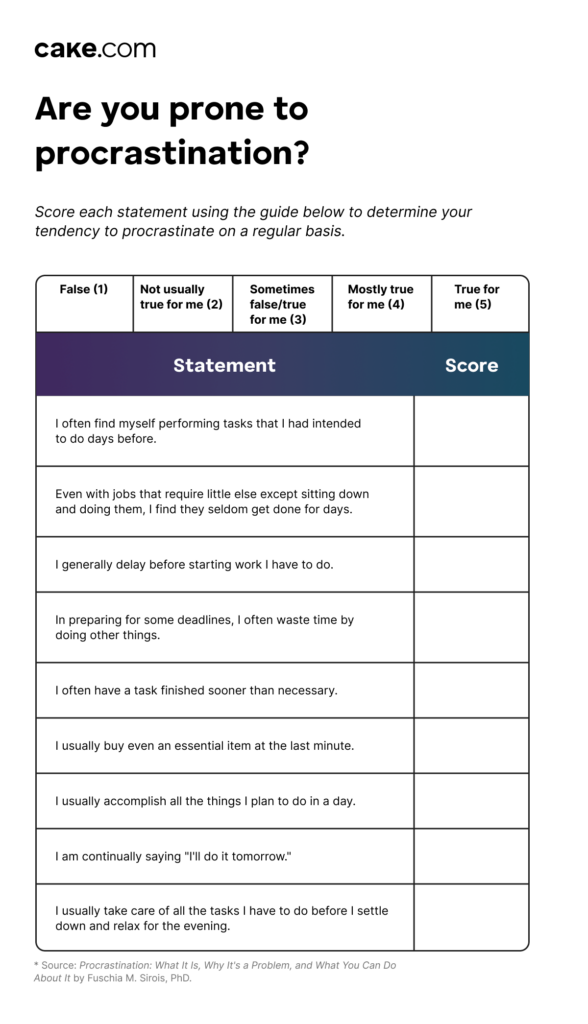

Exercise: Could you be a procrastinator too?

Now, indulging in task delays from time to time doesn’t automatically make you a chronic procrastinator. However, you can check whether you have a tendency to hide from negative emotions and procrastinate.

In their paper on measuring procrastination, Sirois, Sisi Yang, and Wendelien van Eerde developed and validated a simple exercise that could help you determine how prone you are to procrastination.

The chronic procrastination exercise, which also appears in Sirois’ book, is a short version of Lay’s General Procrastination Scale. The exercise consists of a number of statements that help assess people’s procrastination inclinations on a regular basis, such as:

- “In preparing for some deadlines, I often waste time by doing other things.”

- “I am continually saying ‘I’ll do it tomorrow.’”

- “I generally delay before starting work I have to do.”

To find out how prone you are to procrastination, score each statement with the appropriate answer:

- False — 1,

- Not usually true for me — 2,

- Sometimes false/true for me — 3,

- Mostly true for me — 4, and

- True for me — 5.

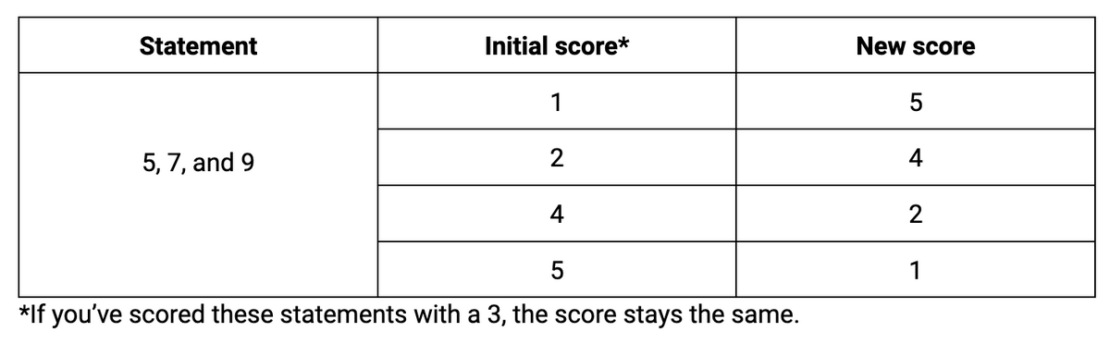

The only exceptions are statements 5, 7, and 9. After the initial scoring, here’s how to reverse score them to get an accurate result:

Once done, sum all the scores and divide them by 9. Refer to the list below to see what your score means:

- Low levels (1.0 – 2.0) — procrastination isn’t a regular habit for you.

- Moderate levels (2.1 – 3.5) — procrastination isn’t a regular habit for you, but you probably delay tasks more than you’d like.

- High levels (3.6 – 5.0) — you often delay unpleasant tasks or tasks that serve as negative emotional triggers for you.

How do you stop procrastinating?

Accepting that you’re struggling with procrastination is the first step toward recovery. However, to overcome procrastination, you’ll have to set off on a journey of changing your mindset.

That’s precisely where mindfulness, self-compassion, and your future time perspective come into play.

Tip #1: Find out WHY you’re procrastinating

Finding the source of the negative emotions you’ve tied to the tasks you’re avoiding can prove to be a challenge. That said, techniques such as mindfulness could help you out.

Though she recognizes that not everyone would like mindfulness, Sirois sees it as a good avenue to explore when struggling with procrastination:

“Mindfulness isn’t for everybody, but you could go for a walk in nature, which can help you clear your head and feel more connected. Because procrastination is about disconnection — we disconnect from the emotions, we disconnect from the task, from ourselves and our goals, [and] our wishes and dreams.”

While practicing mindfulness, we should do some soul-searching, identify the negative emotions that urge us to procrastinate, and deal with them:

“Seek the source. What is that negative emotion, [and] where is it coming from? Perfectionistic feelings, emotional time traveling, lack of sense of meaning, being too hard on yourself, being too worried about what other people think — there are a number of different sources in terms of our narrative that contribute to those negative emotions. So one way [to ease procrastination] is to find what those are and deal with them.”

Depending on the emotions you take note of, you can then employ different strategies to resolve them.

For example, if you’re feeling bad about the tasks themselves, depending on the reason, you could try:

- Reframing them,

- Seeking out more clarity (if you’re not sure how to do these tasks), or

- Breaking them up into smaller, more manageable chunks.

Making tasks more meaningful is another option. It’s much easier to procrastinate on tasks that we don’t necessarily care about too much. However, when the intrinsic value of the task matches our own values and needs, the task gains a meaning that inspires us to work on it — not delay.

Tip #2: Be KIND to yourself

Another important factor to consider when going up against procrastination is — how are you treating yourself?

Though it may seem counterintuitive, Sirois’s research has shown that chronic procrastination is linked to lower levels of self-compassion. So, by helping yourself become more self-compassionate and forgiving about your delays — you just might get better at resisting procrastination.

Unfortunately, self-compassion is deeply underrated as it’s often confused with laziness, irresponsibility, or just plain self-indulgence. But the alternative is guilt — and according to Sirois, guilt certainly won’t help you ease procrastination:

“Guilt does not work to solve procrastination. It makes it worse. So a way to resolve that is to take the flip side, which is where self-compassion comes in. Self-compassion is learning to talk to yourself, listen to that negative narrative, and [consider] if you would say that to a friend.”

Something that could help you learn self-compassion is recognizing that procrastinators aren’t unique in their struggles. Indeed, it’s a common human experience, according to Sirois:

“You’re going to procrastinate sometimes — [but] you’re not alone. That doesn’t make it OK to procrastinate, but there shouldn’t be that much shame around it. . .We try to hide it because of all those societal norms, and we think other people are getting on with everything when we’re not — when actually, people are procrastinating all the time and struggling with it. It is a struggle and a part of being human.”

Tip #3: Embrace your FUTURE SELF

But it’s not just about being kind and caring about your Present Self. All temporal versions of you deserve the same treatment.

As unconventional as it may seem, we could also ease procrastination by closing the emotional gap between what Sirois calls in her book the “Present Self” and “Future Self” — or rather, the Self that’s delaying the task and the Self that’ll pay the ultimate price of procrastination.

The disconnect between our temporal selves makes it so much easier to ignore the future — or even pretend it’s none of our business.

However, by prioritizing short-term mood relief and the Present Self at the expense of the Future Self, we essentially prolong the mental suffering caused by procrastination and its consequences.

The solution? It’s not focusing on the one or the other — but rather avoiding making distinctions between your temporal selves.

After all, all those versions of you matter. And if you show them all compassion, the emotional gap and tension between your Selves — and your chances of procrastinating — should diminish.

Manage your emotions — and you just might resolve procrastination too

Now that you know why people procrastinate, it’s high time you tackled your emotions and got stuff done.

Even science says that procrastination doesn’t do much good, no matter the relief it provides when you feel overwhelmed.

So, try another tactic if you’re struggling to start working on your tasks.

Whether you’re anxious about a task or feel insecurity creeping up, show yourself some kindness and reframe the situation so that it feels less dangerous for you. Trust me — your Future Self will thank you!

One of the many side effects of procrastination is lower productivity. To effectively combat your loss of productivity while resolving your procrastination habits, try the CAKE.com Productivity Bundle now.

How we reviewed this post: Our writers & editors monitor the posts and update them when new information becomes available, to keep them fresh and relevant.