Today, an average worker needs to work 11h per week to produce as much as the one who worked 40h per week in 1950.

Still, even though our working hours have exponentially decreased over decades, that doesn’t necessarily mean our productivity levels have dropped too.

Let’s go over the most recent data regarding working hours throughout history and take a look at average workweeks across the globe.

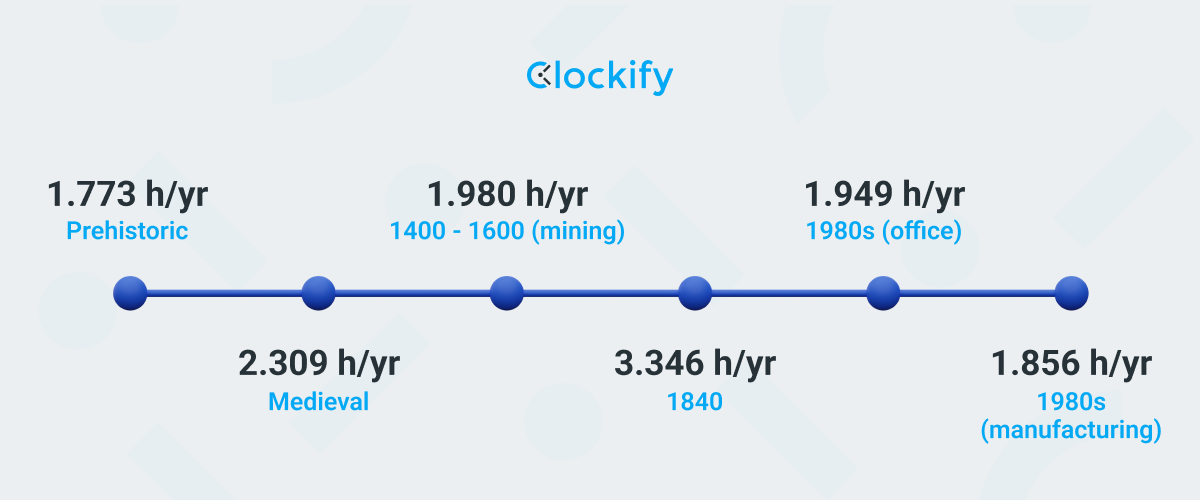

Working hours through history

Compared to the average 19th-century workweek, employees now work 20 to 30 hours less.

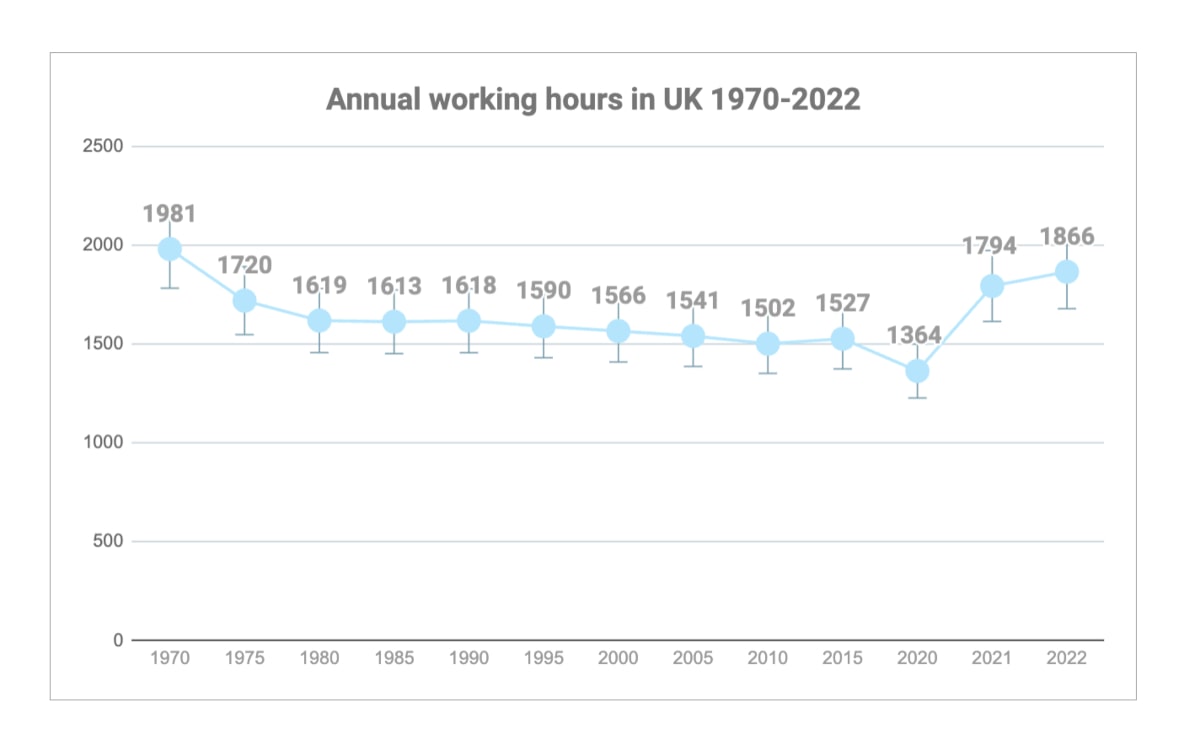

Even though an 1870s worker used to work up to 3,000 hours per year, a decline in annual working hours began back in the 1980s, when the average working hours dropped to 1,949 hours per year.

As time went on, the number of working hours continued to drop.

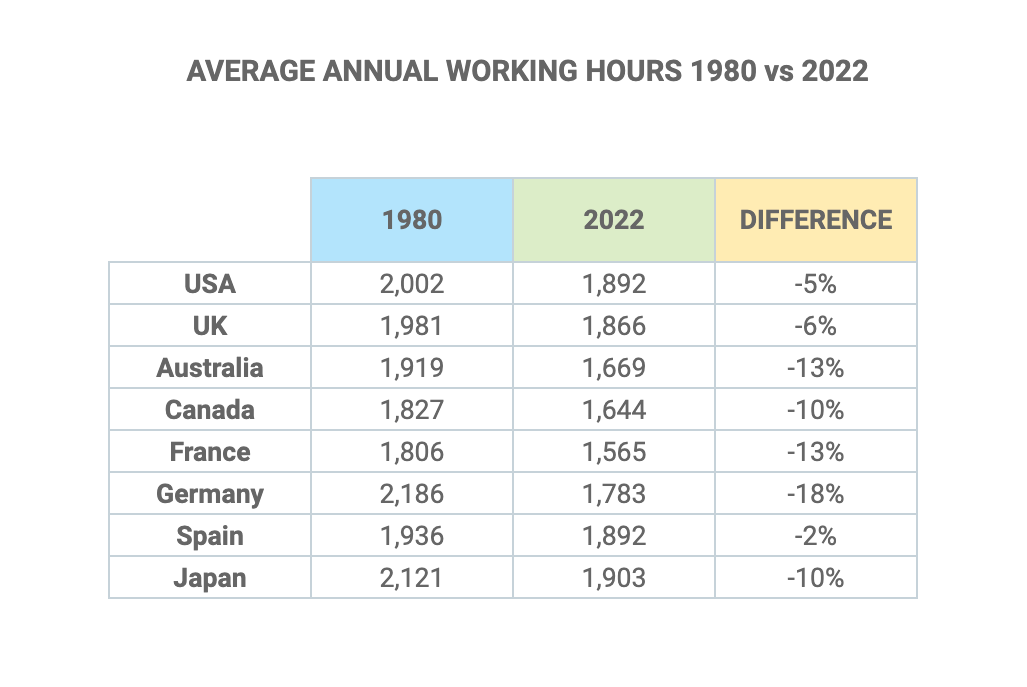

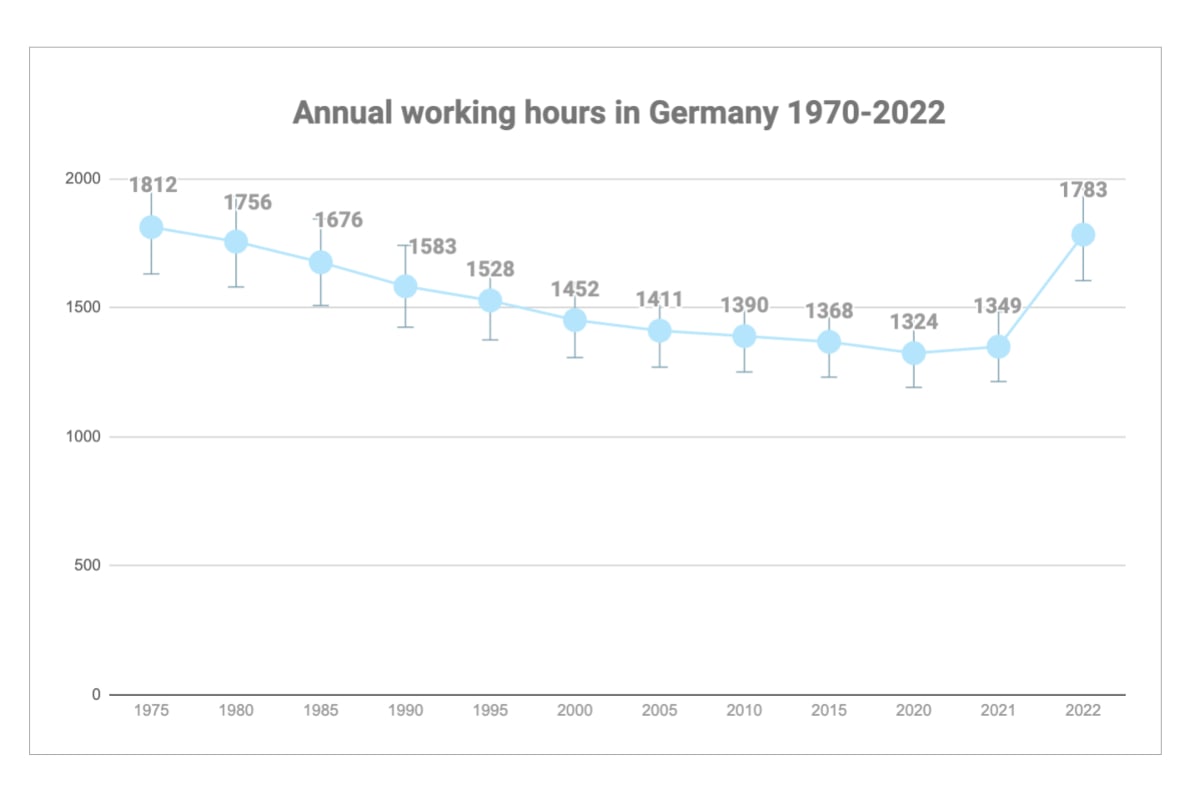

For example, by looking at the average annual working hours across the globe in 1980 and 2022 side by side, we can notice a substantial decline that happened in only four decades.

The greatest decrease in working hours (-18%) can be seen in Germany. An average German worker spent 2,186 hours per year working in 1980 and 1,783 hours in 2022 — which amounts to 403 hours less than in 1980.

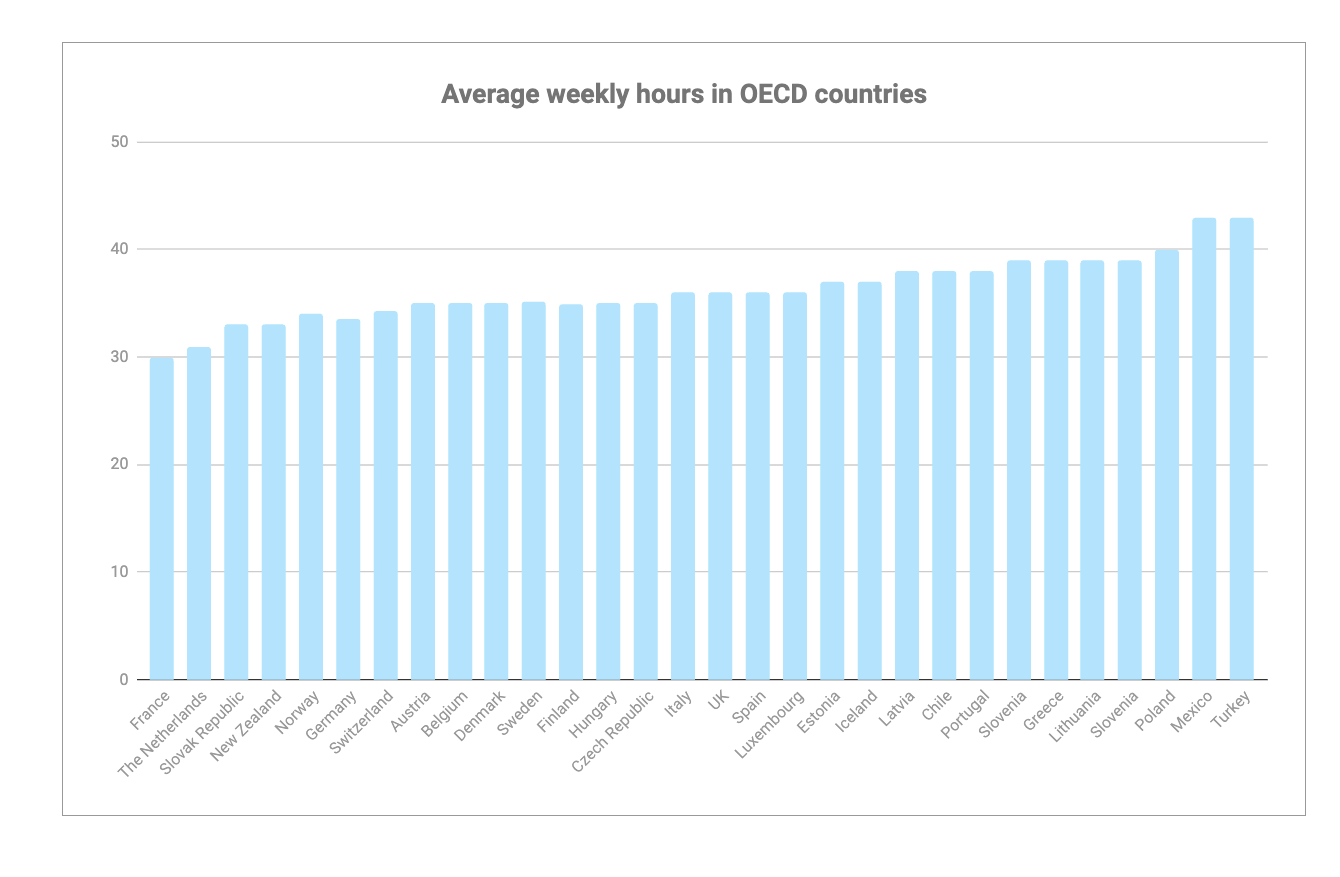

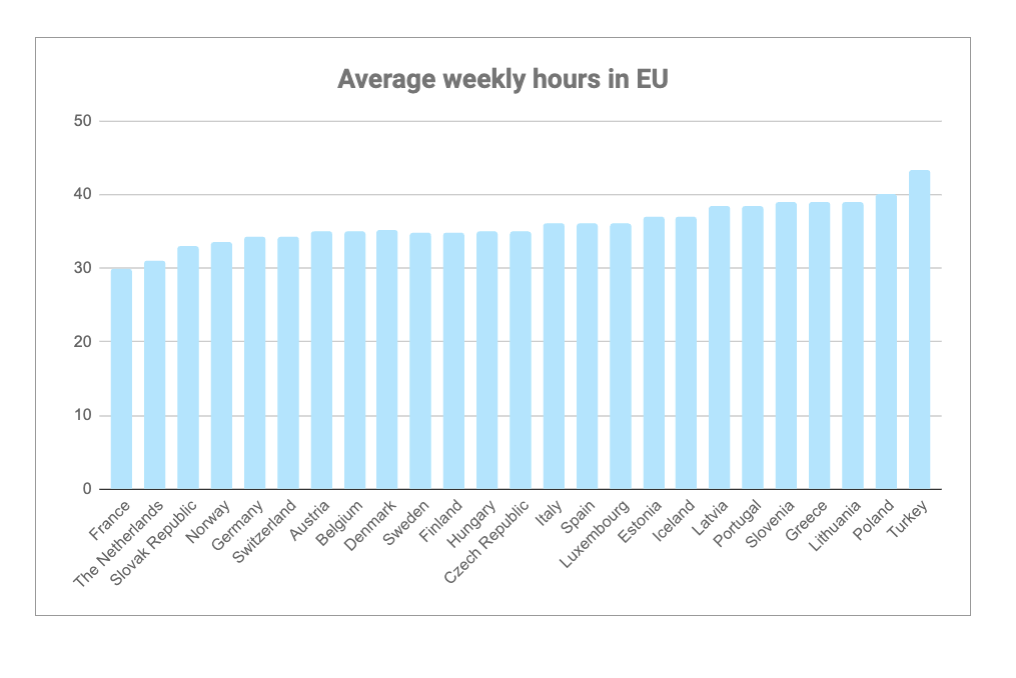

Working hours by country

Even though employees today spend drastically less time working than they did in the past — their average annual working hours significantly differ depending on the country they live in.In OECD countries (i.e. countries tied to The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), for example, a full-time employee works 36 hours per week — which translates to an average of 1,854 working hours per year.

An average full-time employee in the European Union works 36 hours per week.

Moreover, a full-time employee in the United Kingdom works 1,866 hours per year or 35.9 hours per week.

In Germany, full-time employees work an average of 1,783 hours per year or 34.3 hours per week.

An average full-time employee in the United States works 1,892 hours per year or 36.4 hours per week — which is 10 hours per year more than workers from the EU.

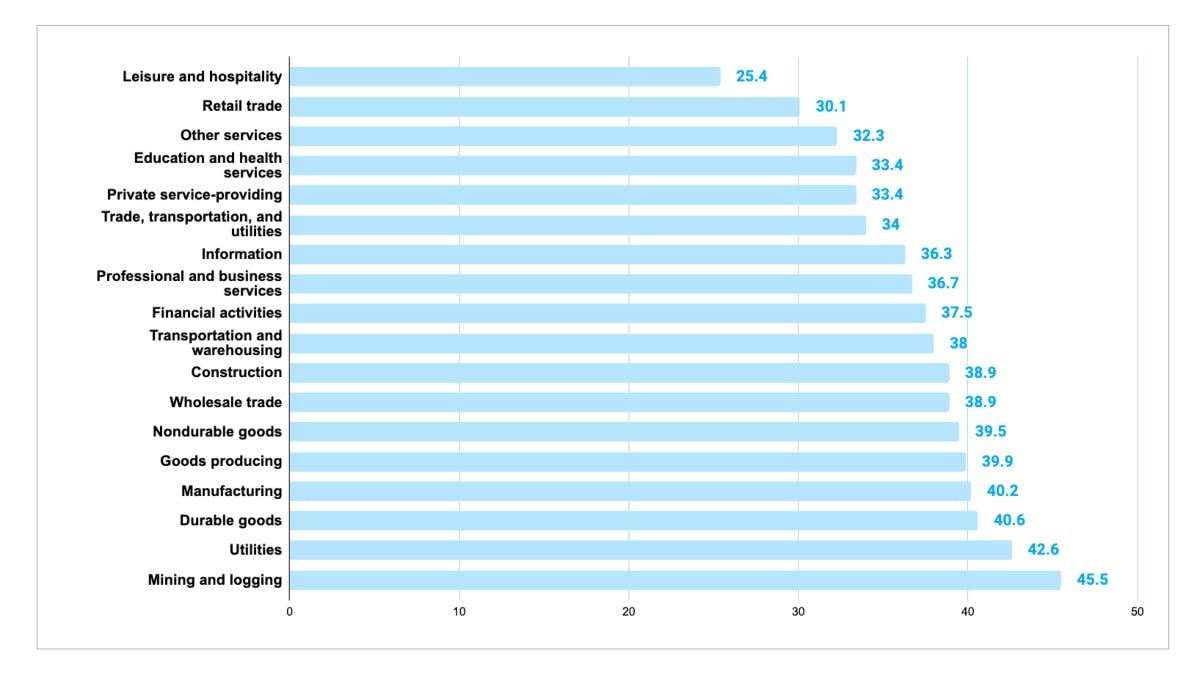

However, US employees’ working hours vary depending on their labor industry.

For example, while workers employed in the mining and logging industry worked 45.5 hours per week on average in April 2023, leisure and hospitality workers spent 25.4 hours per week at work.

Annual working hours by city

Depending on the city of employment, workers worldwide spend different amounts of time at work.

Let’s go over the average annual working hours in 40 different cities around the world:

| City | Number of hours per year |

|---|---|

| Copenhagen | 1,380 h |

| Oslo | 1,384 h |

| Berlin | 1,386 h |

| Amsterdam | 1,440 h |

| Reykjavik | 1,454 h |

| Paris | 1,505 h |

| Zurich | 1,556 h |

| Brussels | 1,586 h |

| Ljubljana | 1,593 h |

| Stockholm | 1,605 h |

| Buenos Aires | 1,609 h |

| Vienna | 1,611 h |

| London | 1,668 h |

| Barcelona | 1,686 h |

| Ottawa | 1,689 h |

| Tokyo | 1,691 h |

| São Paulo | 1,707 h |

| Rome | 1,717 h |

| Sydney | 1,726 h |

| New York | 1,765 h |

| Dublin | 1,772 h |

| Auckland | 1,779 h |

| Prague | 1,787 h |

| Bucharest | 1,792 h |

| Istanbul | 1,832 h |

| Faro | 1,865 h |

| Tel Aviv | 1,900 h |

| Santiago | 1,914 h |

| Medellin | 1,968 h |

| Jakarta | 2,020 h |

| Warsaw | 2,022 h |

| Athens | 2,036 h |

| San Jose | 2,069 h |

| Taipei | 2,085 h |

| Bangkok | 2,093 h |

| Delhi | 2,123 h |

| Mexico City | 2,137 h |

| Lima | 2,140 h |

| Hong Kong | 2,147 h |

| Singapore | 2,330 h |

Employees from Copenhagen, for example, spend the least amount of time at work — only 1,380 hours per year.

Singapore workers, on the other hand, work almost twice as much — they spend 2,330 hours per year at work.

Weekdays and paid time off by country

Even though the usual workweek is from Monday to Friday in most of the world, some countries work 6 days per week, whereas some, such as Canada and Belgium, have introduced a 4-day workweek.

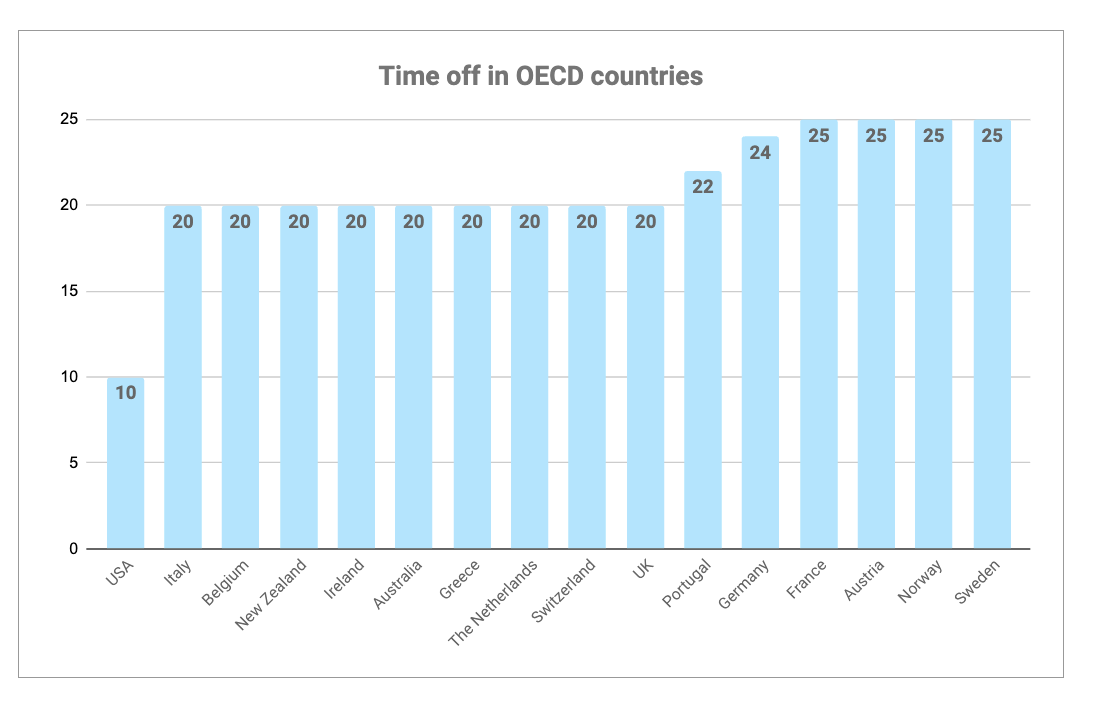

Also, many countries have a legally mandated maximum workweek, except for the US.

The US is also the only developed country that does not legally mandate its citizens paid vacation — as opposed to European employees who are given at least 20 days of paid leave per year.

Productivity and working overtime

Productivity levels do not simultaneously grow with increased working hours.

As a matter of fact, it’s quite the opposite.

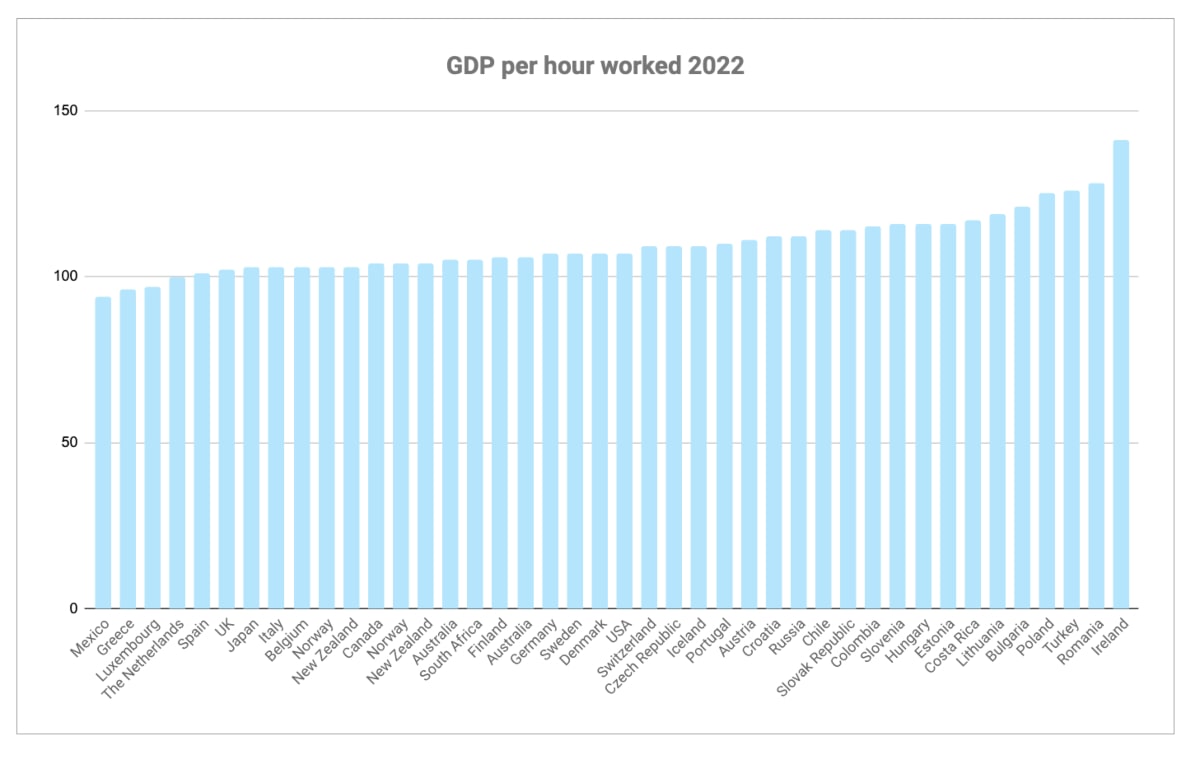

By looking at the average GDP per hour worked, it can easily be seen that an increase in working hours is almost necessarily followed by a productivity decrease — as is the case with Mexico.

Namely, even though employees from Mexico spend 42 hours per week at work, their GDP per hour is among the lowest in the world.

Workers in Ireland, on the other hand, work 36 hours per week on average — but their GDP per hour is the highest in the world.

However, although our productivity levels today are at their highest level than ever before, and work hours have been exponentially decreasing over time too, overtime is still a common practice.

Namely, research has shown that 1 in 10 employees worked an extra day of unpaid overtime every week in 2021.

Quiet quitting and its impact on employee engagement

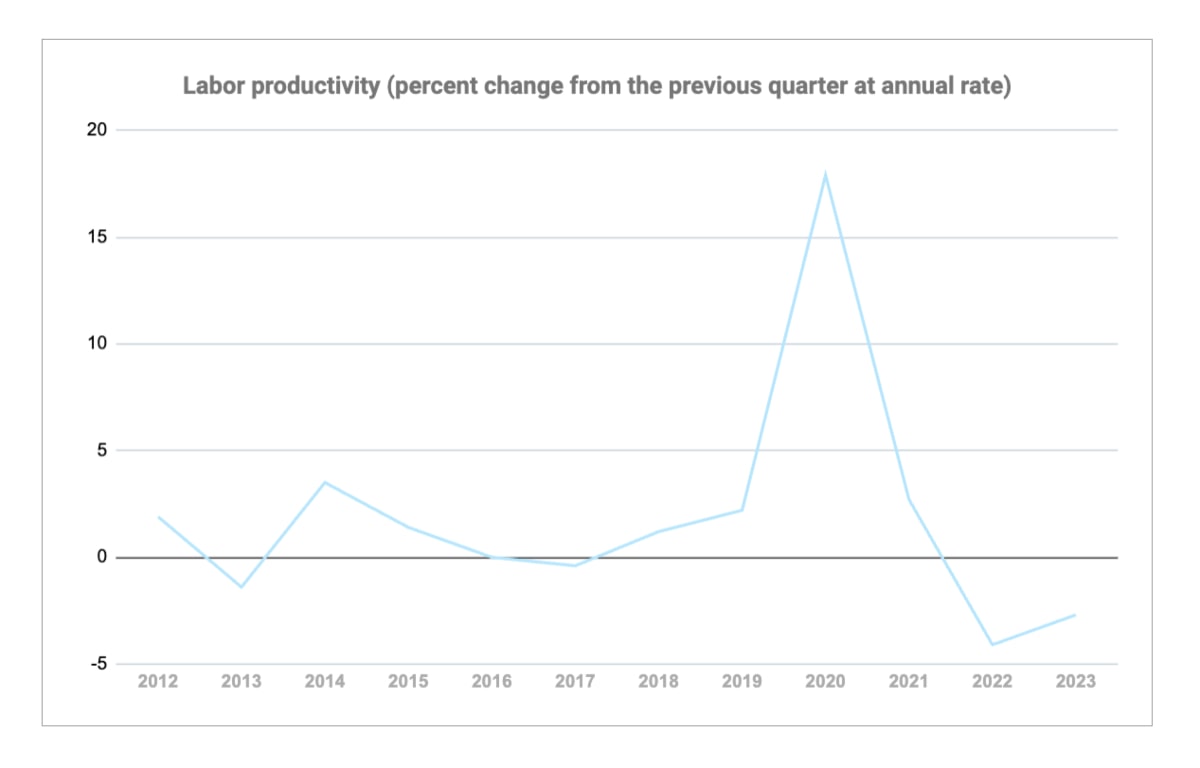

Partially due to overtime being on the rise, in Q2 2022, US employees demonstrated the lowest drop in productivity ever since the US Bureau of Labor Statistics began tracking employee productivity in 1948 — 4.1%.

In 2023, the negative productivity trend continued, and the US workers’ productivity dropped by 2.7% in the first quarter of 2023.

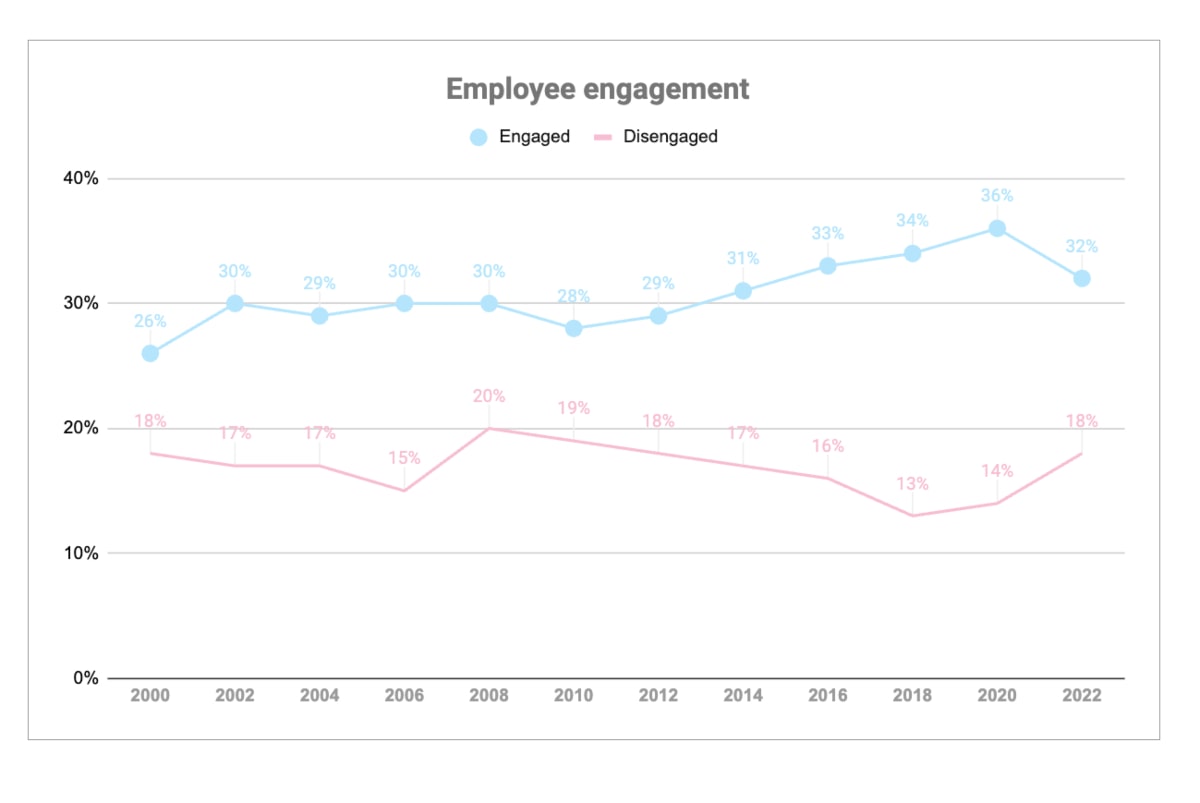

This drop in productivity, coupled with an increased number of actively disengaged employees across the US, could mean quiet quitting is flourishing.

Research has shown that more than 50% of US employees have already embraced the quiet quitting phenomenon. Based on this, the productivity decline shouldn’t come as a surprise since performance outcomes and engagement rates are strongly tied to employee productivity.

____

*The average working hours in this summary are the average weekly hours provided by the International Labour Organization, multiplied by 52.

Further reading

This is just a summary of an article previously published on the Clockify resource page.

To find out more detail about the working hours statistics, we recommend reading the full article: